“The truth is, usually the best underscore is invisible.”

‘Spoken’ by David Hirschfelder, these few simple words in form but not meaning struck a deeply resonant ‘chord’ which stretched beyond the parameters of scoring for film. Too deep maybe?

Let me back up a little. Some weeks ago, as I scoured the internet for meaty background info on the composer, I unearthed a fair amount of written material, but apart from an eternity of videos uploaded from all across the globe showcasing an enormous body of work, footage of Hirschfelder talking (not playing), was almost non-existent.

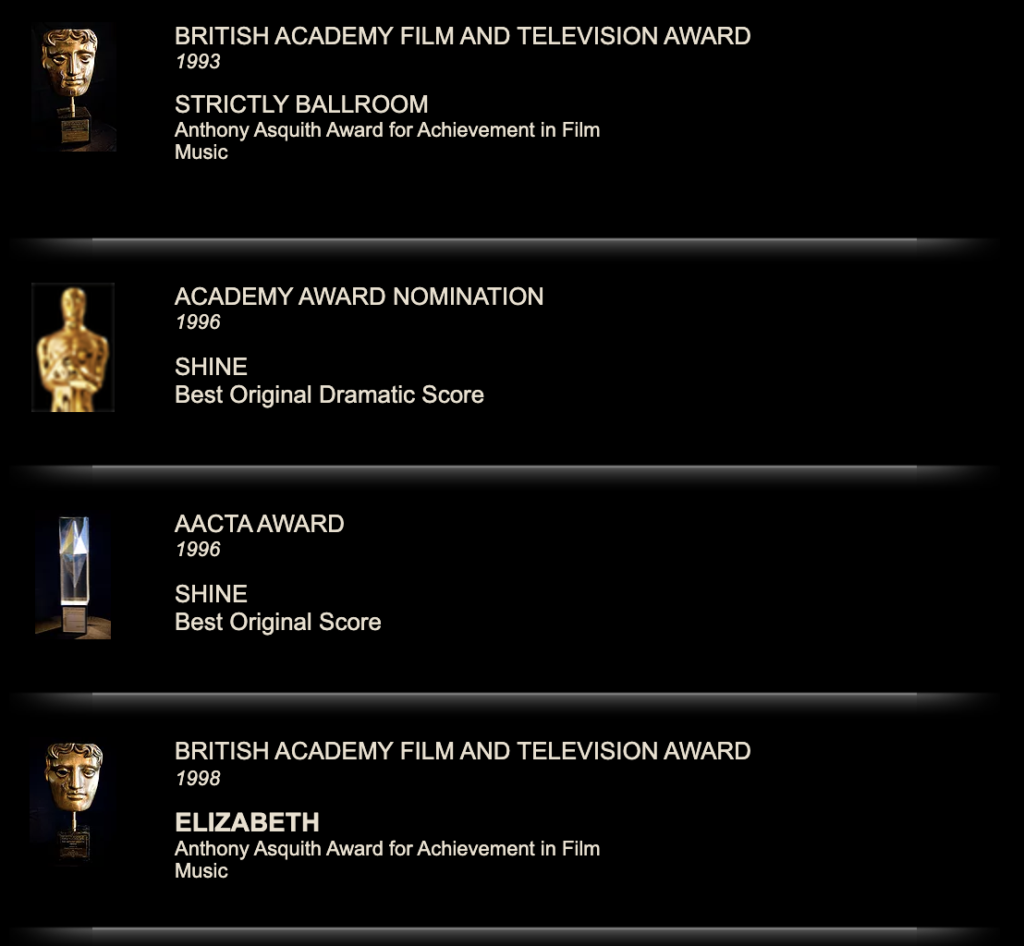

Perhaps, voyeuristically, I had hoped to gain a little more insight into the person behind that great wall of award-winning composition, but this proved to be inessential. As you may gather from the interview below if you choose to read on (and I hope you do), Hirschfelder conveys his decades of knowledge, experience, intelligence, and thoughtfulness as well as a lovely warmth.

Rewind a little more. I’ve been an admirer of Hirschfelder’s talent since my uncomfortable days as a gawky, badly-permed 80s student of music culture and still am, which is why it is such a pleasure for me to share with you, even a small window into the man and his work (…and thankfully I’ve lost the bad perm).

Yes, the best underscore may be invisible but the truth is, the extraordinary human being behind it, is not.

Wiltshire: Thank you so much for your time, David. it’s such a pleasure to chat with someone whose talent abounds and a fellow Aussie! I hear you first awakened to the beauty of cinema and score after watching “Exodus” at the ripe old age of 6. That inspired you to pick out the theme on your grandmother’s old upright piano. Were there other instruments competing for your attention or was piano the clear winner? If it had been a zither, would we now be hearing a very different Hirschfelder story?

Hirschfelder: Well it’s probably fortuitous that my grandma had a piano, an instrument that also happens to be a composer’s typewriter. The notes are conveniently laid out in a nice linear row from lowest to highest, and so convenient for an inquisitive child to pick them out. It’s also an orchestra in a box, so with just a little practice, or even just mucking around, you can soon learn to combine left and right hands to form chords, rhythms, and melodies, the basic building blocks of music. As you’ve noted, the piano has been a lifelong friend of mine, but being a composer, I have no real favourite instruments. There are so many characters on offer from a wide range of western orchestral instruments, as well as all the “exotic” instruments that spring from our multi-cultural world. And now we have electronica too! But it’s funny that you mention zither, because I do like a good zither, and have been known to utilize it from time to time!

Wiltshire: Have you come from a musical lineage and therefore instinctively guided to and through the process of discovery or are you the vocational black sheep of the family?

Hirschfelder: There’s music in my DNA, for sure. My Oma (grandmother on my father’s side) was a brilliant classical pianist in Germany prior to WWII. She could also improvise and compose. Unfortunately, the war put a stop to her career. My mum has a magnificent soprano voice and she can also play piano; she was active in local choirs, music theatre, and opera, though she never pursued music professionally. My father could play piano by ear, but he had no formal training and never developed his latent musical talent. My parents both loved music, and always provided me the best possible musical education and a huge amount of support and encouragement.

Wiltshire: For those of the seven billion around the globe who have never heard of Ballarat, your hometown, it’s a city approximately 100 kms NW of Melbourne, Australia (my hometown). Given the relatively small population, do you have an explanation for the abundance of talent from there (including yourself), other than Melbournians in my circles saying, “there must be something in the water”?

Hirschfelder: Yes, there could be some magic in the hills of Ballarat, some mystical quality from the extinct volcanoes, or whatever other metaphysical theories you may fancy. It could be all that fresh air! The tap water in Ballarat does not taste very good to be honest, probably due to the high mineral content from the volcanic soil. But I suspect the high proportion of artistic talent springing from Ballarat might have a lot to do with the town’s long-standing of passion for (and commitment to) the performing arts, and art in general. Ballarat balances the beauty of rural lifestyle with the benefits of urban cultural diversity. So that thing “in the water” undoubtedly refers to the great vibe of Ballarat, with it’s stimulating artsy community, wonderful schools etc., all located in a beautiful environment, elevated amongst hills, with lots of trees, and a gorgeous lake!

Wiltshire: As the keyboardist for Australian artist, John Farnham through the 80s, you contributed significantly to writing, arranging, recording and performing the songs which created such a distinctive sound and complexity not always found in the pop arena. Many of these, including the formidable, musical nexus, “Playing To Win”, went on to become chart-topping hits. Were you ever told to “dumb it down”? And did the roadies shudder with fear or anticipation at your imposing keyboard rig?

Hirschfelder: John Farnham and I first met as new members of the Little River Band in 1983. It was an exciting time of change and growth for both John and I, and for LRB. Musically we all had a lot in common, and “Playing To Win” typified our musical direction — a blend of rock energy with a few added neo-classical hi-tech overtones. My influence and musical bent was welcomed in LRB, and by John. I was never asked to dumb it down. Spencer Proffer, US producer of the LRB “Playing To Win” record always encouraged my input and individuality. I remember Spencer once gazing into the green glowing screen of my Fairlight (early music computer, for composing and sampling — invented circa 1980 in Australia!), and all the knobs on my various synthesizers and keyboards, saying “I have no idea what you’re doing with all this stuff, but I’ll just give you free reign over my studio and all my staff — just do whatever you want, man.” Similarly, I was given a lot a creative freedom with John Farnham’s “Whispering Jack”, “Age of Reason” and “Chain Reaction” albums. I had amassed a lot of gear by the late 80s, including a Fairlight CMI Series II music computer, two Yamaha QX‑1 eight-channel midi sequencers, a Prophet 5 analogue synth, a Yamaha DX7 FM digital synth, a Yamaha KX5 Keytar, a Korg PolySix analogue synth, a Yamaha CP80 electric grand piano custom modified with midi, Fender Rhodes 88 electric stage piano, three racks of various synth modules, effects processors, and amplifiers, all going through three Yamaha DMP7 midi programmable eight-channel digital mixers. It was a sort of (not so) portable electronic music studio really, so yes, the road crew were brave and incredibly wonderful hard-working souls, who never complained, but no doubt had to endure a lot of physical challenges lugging all this equipment around and setting it up on stage every night!

Wiltshire: Was there a particular catalytic event (or person) which presented the opportunity to move from composing for TV to your first (and BAFTA-winning) score for Baz Luhrmann’s “Strictly Ballroom”?

Hirschfelder: Although I had already scored a few TV dramas and documentaries by 1990, I was at that time still known mainly for my keyboard performing and production work with John Farnham. However, an old school friend of mine, opera singer David Hobson (also from Ballarat — go Ballarat once again!) had just been working with Baz Luhrmann on his Australian Opera production of La Boheme. At that time Baz was an opera director, but also writing and developing a feature film, and was looking for someone with a multiple musical skill set to be musical director, arranger, and composer. Being familiar with my work as a keyboard player, music producer, bandleader and TV composer, Baz had asked David (nicknamed “Hob”) about me, wanting to know whether or not I had film-scoring orchestral chops. Hob confirmed that I was indeed classically trained, could write and arrange for orchestra, and that I was also a reasonable human being 🙂 so — thanks to my old school Ballarat buddy Hob giving me a glowing reference, Baz telephoned one day and offered me my first feature film score, Strictly Ballroom — also Baz’s first feature film.

Wiltshire: Strictly Ballroom, was also the first film you scored on a computer using Logic Pro. How steep or impactful was the learning curve as you worked to your deadlines? And the nerdy question for the benefit of the many producers out there, is it still Logic or ProTools?

Hirschfelder: Ok, first to clarify, the scoring software I used for “Strictly Ballroom” was Performer (as it was then known, prior to becoming Digital Performer in the early nineties). Luckily for me on my first outing as film composer, “Strictly Ballroom” had a generous schedule that lasted almost a year, which was plenty of time for us newbies to navigate our learning curves. First I had to help put together click tracks and determine style, and tempo, for various choreographic sequences. Then I took a few weeks off to tour Europe with John Farnham, while “Strictly” was being shot. I arrived back from Europe just in time to finalize the temp tracks for the Pan Pacific Dance Competition shoot in Melbourne. And then straight after that, the film went into post-production. It was a steep learning curve and a huge creative challenge for both Baz and I, due mainly to us being such a small team, having to wear so many hats. There was no music supervisor or music editor, so we had to do all copyright clearances ourselves, and I had to conform the score to the ever-changing cut, learning the craft of music-editing, flying by the seat of my pants. Given the limited budget available for licensed music recordings, I had to replace a lot of the more obscure dance music with original music to save money. Luckily, the two fantastic John Paul Young songs “Love Is In The Air” and “Standing In The Rain”, were published by Alberts (who were also the main financiers and executive producers of the film) so we could use these gratis pro bono, as well as parts of the recordings, such as some instruments from the original multi-track tapes and JPY vocals; but they still required re-arranging and adaptation for the film. There were also many traditional music elements, such as flamenco guitars, which were recorded on location, and then chopped up and “revamped” later using an Akai S1000 rack mounted sampler, hooked up (along with many other samplers and synths) to an early Mac computer running Performer sequencing software.

Getting back to that nerdy question of software, in 1992, for the recording and live production of Jesus Christ Superstar, I switched from Performer to the now-defunct Studio Vision. But unfortunately, due to the parent company of Studio Vision going bankrupt around 1995, I was then forced to switch platforms again. Thus, Logic Pro has been (and still is) the centre of my composing rig since the film “Shine”. Logic is great, in that it was one of the first music software packages to successfully integrate midi-based composition with notation, audio processing, and movie files, all in the one package. I do also like to use Pro Tools for audio editing, and also for audio recording, mixing, and final delivery, mainly because Pro Tools is the industry standard platform utilized by sound engineers, music editors and film re-recording mixers, so it’s handy to be proficient with Tools.

Wiltshire: One of my all-time favourite soundtracks is the Oscar-nominated, “Shine” which never fails to keep me teetering between feeling euphoric and wretched. What elements come into play when deciding whether or not to take on a project, which inevitably consumes a major portion of your life and mind? Is there more appeal for you in being driven creatively by a powerful, gut-wrenching story such as “Shine”?

Hirschfelder: “Shine” was a huge milestone for me, a pivotal turning point in my career. The script (first sent to me for consideration in 1993) was sheer brilliance, and truly unique. I have never read any script like it, before or since. Given I am a musician who had experienced the stress and pressures of performing classical works on piano live onstage, from memory, the story resonated so strongly and personally with me that I was utterly compelled, thrilled and deeply honored to accept Director Scott Hicks’ offer (and challenge) to fill the roles of music curator, music director and score composer for this amazing true story. Having just spent over a decade being a sort of accidental tourist in the world of popular contemporary music, it was so satisfying to reconnect with my classical roots. I also agreed to be script-consultant, regarding classical terminology, suggesting the sort of things a music teacher might say to a student; for example, “Play it slowly David, it’s not a race!” Or as David’s piano professor said in the film, describing Rachmaninov’s Concerto No. 3 “It’s a monster! Tame it, or it will swallow you whole!” Then a little later, as the film shoot approached, I had the great pleasure to work with David Helfgott, the man whose true story is the basis of the film “Shine”. We recorded David’s piano performances in various locations, on many different instruments, and later refined, adapted and synchronized the recordings to the film. But undoubtedly the most deeply rewarding aspect of working on this soundtrack was the creative opportunity to create an original score that interconnects and coexists with the titanic works of Rachmaninov, Liszt, Chopin, Vivaldi, and Beethoven!

08:00 — Hirschfelder describes the process of scoring from computer to orchestra while working on feature film, “Australia”.

Wiltshire: Can you describe how you felt the very first time you heard an orchestra play your work?

Hirschfelder: The first time an orchestra plays something formerly unheard (other than in one’s head, or as a clinical computer mock-up), it can be terrifying and thrilling all at the same time. Is my composition or orchestration going to work in the real world?? Sometimes the orchestra may take a few run-throughs before difficult angular melodic motifs and interlocking rhythms come together. Sometimes challenges for players arise when an inexperienced orchestrator writes parts that are verging on unplayable. Such was the case for one of my early experiences, in 1988, when John Farnham toured Australia with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra. During the first rehearsal, the orchestra’s first playback of my arrangement for “Playing To Win” sounded a little rickety, due to the rhythmic challenges presented for such a large ensemble. However, after they played it a couple of times, it started to sound more confident, exciting and quickly turned into something utterly exhilarating. It was cathartic to hear the things I had written on paper come to life, manifesting before my eyes (and ears) into some sort of giant wildly undulating mythological beast!

Wiltshire: Is there a particular way of communicating ideas which connects with you more successfully than others when working with a film director as they convey their vision, passion, and goals to you? Do you prefer broad strokes, specifics, or perhaps a combination?

Hirschfelder: I have no preference at all for a music brief; just as happy with broad strokes, or specifics. Usually one gets a general overview, the broad brush strokes of the director’s vision for the style, character and desired functionality of the score. Sometimes a director, or producer, or film editor, may have specific ideas to enhance details on the screen with music. On rare occasions specific score ideas might be in the form of suggestions regarding instrumentation, dynamics, or style etc., but more often than not, such ideas are demonstrated via a temp music score that has been crafted to fit the pictures, or perhaps the pictures themselves might be cut to hit with the temp score. A good filmmaking team will be able to convey both verbally and also by audio demonstration using temp score. This is useful provided the filmmakers aren’t too MARRIED to the temp and are open to a new interpretation of the score. Then, on other occasions, I’ve been presented with the film with absolutely no score at all, and on rare occasions, you’ll find a director who is not at all particular about musical direction, simply happy to leave it to me. So, as you can see, it’s important for a screen composer to be flexible and adaptable to the many potential ways one might be briefed, or even not briefed.

Wiltshire: As a creative, one of the toughest things I have to do is constantly present my work for examination and critique. How do you remain objective when the director or client feels you haven’t nailed it and you feel you have? Or has that never happened? 😉

Hirschfelder: I hear you, and feel your pain, when it comes to coping with examination and criticism, be it constructive, or otherwise. And yes, of course, that has happened 🙂 However, after much experience, and even a little therapy, I have come to realise that even as one gets better and more experienced at one’s craft, the phenomenon known as RE-WRITES is never going to go away. It’s always going to pop up from time to time. But here’s the thing; why fight it? I’ve learned that I can’t control the outcome, I can only control the process. I can’t control whether or not an audience likes, or GETS, the music I write. But I can listen to them, and be open, embrace the feedback, LEARN from it. That way I grow, find new ways to connect with an audience, and get the chance to do another draft that could be even better. And even if it’s not really any better, just different, and even if the re-write simply ticks imaginary boxes that don’t really matter, then even THAT scenario can feel like a creative triumph, because you’ve won the game, pleased your colleague(s), and most importantly, kept your sanity (and your gig) intact. Better to think of it like this: I like writing, so I’m always happy to re-write, make changes, and enjoy having another go!

Wiltshire: You met with director, Shekhar Kapur, at a crowded Soho café in London where you immediately “heard” the soundtrack as he described the opening scene of “Elizabeth”. I love that when he asked you to play the idea on the café piano, you obliged. Did the rest of the soundtrack come together as easily?

Hirschfelder: During the early phase of post-production, the score for “Elizabeth” was really challenging to write, and I was initially way out of my comfort zone. I had just finished mixing an epic collaboration in New York with my old friend operatic tenor David Hobson (yes “Hob” in my life again), a contemporary classical crossover album titled “Inside This Room”. I was in need of a break, exhausted mentally and physically. However, the “Elizabeth” schedule required me to immediately relocate my rather large digital audio workstation to London and start writing the score for “Elizabeth” ASAP. As the saying goes, ‘the best things in life are never easy’, and the picture cut also struggled to find it’s feet in the editing room. Renowned UK music editor Mike Higham, my associate on “Elizabeth” said early in the process, ‘this is a hard film to score’. But after weeks of struggle, we found the right musical path. Shekhar came up with the inspired idea of replicating the ‘Soho House Epiphany’ (as mentioned in your question) by booking time in a studio at a grand piano. Incidentally, it was the Imperial Bösendorfer on which Freddie Mercury recorded “Bohemian Rhapsody” so that piano had quite a VIBE! Anyway, Shekhar sat beside me, at this piano, in the London recording studio, and with his hypnotic voice, described a scene (not in the film!) where evil monks are in a chapel, dancing around a ceremonial fire, chanting in rapturous devil-worship, a satanic mass. The mesmerizing dulcet tones of Shekhar’s voice put me in some sort of trance, and I started to improvise on the piano, playing low menacing 6/8 dance rhythms of the Elizabethan-era, and then adding a sombre requiem-like melody, but twisted with tritones, the ‘devil’s interval’, absolutely forbidden in early church music. This piano improvisation was recorded, and with only a little editing, it became the sketch for the Opening Title Theme, and the composition of which was orchestrated with 90 piece orchestra, 40 piece choir. The original piano was kept as a hidden underbelly of the final recording, so you can occasionally hear it growling underneath the orchestra and choir.

David Hirschfelder with James Cameron at the 2011 Premiere of “Sanctum”.

Wiltshire: Any standout dos or don’ts you wish to share with budding composers when working with directors?

Hirschfelder: My biggest DO would be to listen openly, deeply and mindfully to what the director says. Because they are trying to find words to describe abstract concepts of score functionality, their words can be sometimes cryptic, easily misunderstood, the intent can be missed, or misinterpreted. This is why I always record music briefing sessions, rather than just relying on written notes scribbled in real-time during a meeting, so that I can refer back to the recordings, and note the subtext of what they’re saying. For example, the tone of their voice or their choice of words might indicate secret concerns, insecurities about a scene, that they want to be alleviated by score. My biggest DON’T would be to not overreact to criticism or feedback received. The paradox is that you need to be confident in your art and craft, but not fall into the trap of allowing your ego/hubris to tell you ‘hey this is perfect, I don’t need to change a thing’. Remember, as a film composer, you are a collaborator. You’re like an actor giving a performance, creating a character that the director will often want to modify and sometimes even completely change. So yes DO develop and use your strong compositional voice, but DON’T resist change, DON’T listen to the internal chatter of your wounded ego. Also, another anathema to overcome is a fear of deadlines. An important thing to DO is think out of the box in practical and creative ways, find creative shortcuts, lateral solutions to adapt to challenging schedules.

Wiltshire: As an ex-vocal editor (on Logic Pro!), I’m sometimes dragged out of the listening experience when I hear an unpolished edit or an unnatural autotune/melodyne lurch. Are you able to sit and watch a film without analyzing its score?

Hirschfelder: I almost always listen to the score while I’m watching a film or TV show, constantly analyzing the form, sound, and relationship between music and story — EXCEPT — when all the audiovisual elements of the narrative are so perfectly in sync that I become lost in the moment. In other words, when it’s really working, I forget to listen to the score. The truth is, usually, the best underscore is invisible.

Wiltshire: Like many creatives, are you impossible to be around when you take the plunge into that next project? How do you balance family life and break time with the long hours?

Hirschfelder: Yes, I can be moody and temperamental when I’m grappling with the start-up phases of a project. It can be daunting, quite a freak-out to confront the yawning chasm of work-to-be-done, stretching out in front of you. But after a day or two of fearful, even dark moodiness, the sparks of inspiration suddenly kick in. And then, I turn into an antisocial hermit. Fun, right? The hyper-focus of it all means that I am now often unavailable, mentally in another place, almost constantly in my studio, or often vacantly ‘elsewhere’ at meal times. Fortunately, I have a very loving and understanding partner, who has seen this many times. She is so kind, supportive, wise, patient and copes very well with ‘Scary Dave’. But we both recognize the above-mentioned mood-swings and roundabouts, and we can even laugh about it. As she just told me with a smile, “You’re not that bad, darling!”

Wiltshire: As ludicrous as it may sound to the rest of us due to the overwhelming evidence that you’re divinely doing what you’re meant to be doing, have there been any moments of self-doubt where you think, “Crap! Who am I kidding?”

Hirschfelder: I think self-doubts and feelings of “Crap! Who am I kidding?” are a completely normal part of the creative mindset. My ever-faithful manager (best friend and life coach!) has often been supportive in reminding me not to be so hard on myself. The creative mind seems typically to be tidal, quite bi-polar, in nature. Low Tide is when you’re feeling lost, empty, waiting for the inspiration, and then High Tide comes and the endorphins rush as you ride the waves of a natural creative high. Then, inevitably, the low comes back, because what goes up must come down, of course. And so it goes, a constant roller-coaster rising to “I can do it all” self-confidence, only to eventually fall to a low point of “I can’t do it, the magic’s gone” self-doubt. These ups and downs are a completely normal part of the artistic temperament. In fact, this is the locomotive engine that drives the creative mind, so it’s good to keep aware of the up-down continuum and work with it, rather than fear it or fight it.

Wiltshire: Favourite plug-in?

Hirschfelder: This varies, but at the moment, it’s a wonderful virtual instrument by Ventus called Shakuhachi.

Wiltshire: Number 1 takeaway cuisine for those long studio hours (take-out for my American friends)?

Hirschfelder: Indian Curries — HOT!

Wiltshire: A proud moment?

Hirschfelder: During my acceptance speech for AACTA Best Score for “The Railway Man”, it was wonderful to be able to dedicate that award to my father, who had passed away the previous week. Dad was always so proud of me, and I’m certainly proud of him.

Wiltshire: Toughest movie to score?

Hirschfelder: Definitely “Elizabeth”, but the struggle was well-rewarded by a great and highly successful movie, and a score that received an Oscar nomination, and a BAFTA award.

Wiltshire: Favourite movie to watch?

Hirschfelder: Hard to pick a favourite — I love so many. “Ben Hur” (the original 1959 version), “Shawshank Redemption”, “The Fifth Element”, “Baraka”, all the “Star Wars” films, all the “Indiana Jones” movies, to name just a few … I could go on and on!

Wiltshire: Favourite movie to listen to?

Hirschfelder: “The Mission” — Maestro Morricone at his finest. Possibly the greatest film score of all time.

Wiltshire: “If I could be anyone (or anything) for a day, I would…

Hirschfelder: …be a bird … great to be able to fly.

Wiltshire: Before I exit the planet I hope to…

Hirschfelder: …explore India with my beloved.

Wiltshire: Best lost in translation moment as an Aussie in L.A.?

Hirschfelder: Australian music terminology for a unit of time is a “bar”, but in the US, musicians refer to it as a “measure”. In a studio in Burbank, I was conducting the orchestra for our recording of my score for the Kathryn Bigelow film “The Weight of Water”.

As usual I would say things like “let’s pick it up from bar 33”, but because we were in the US, there would be strange looks, grinning, or even a quiet giggle from the players, at my funny accent, and my quaint use of “bar” instead of “measure”. Later in the session, I said again, “let’s all now go to bar 11” to which one cheeky cellist decided to take the piss and asked, “Which bar is that?” To which I replied without hesitation, “It’s the best Bar in Burbank. Excellent Margaritas!”

Hirschfelder at the 2008 Screen Music Awards in Sydney, Australia

Victoria Wiltshire

Victoria began her professional music career as a recording artist with Australian group, 'Culture Shock' after signing to Sony Music in 1993, resulting in a top #20 national single.

Following the success of Culture Shock, she expanded her performing career to musical theater, songwriting and production.

In 2003 Victoria formed a songwriting/production partnership with music producer, now-husband, Paul Wiltshire. Over the following 15 years, the pair wrote &/or produced for The Backstreet Boys, Australian Idol, Engelbert Humperdinck, Guy Sebastian, Delta Goodrem and many more, with sales exceeding 15 million internationally.

Following her writing/production success, Victoria became Creative Director for 360 degree music company, PLW Entertainment, overseeing artist & product development, image design and marketing.

As Chief Experience Officer, Victoria infuses her passion for the creative and innovative into all that she does while overseeing the overall, holistic experience of Songtradr's global ecosystem.

Very good write up, thank you for this Victoria ⭐️ ! Even though I don’t write film scores I found this interview to be interesting and informative to me.